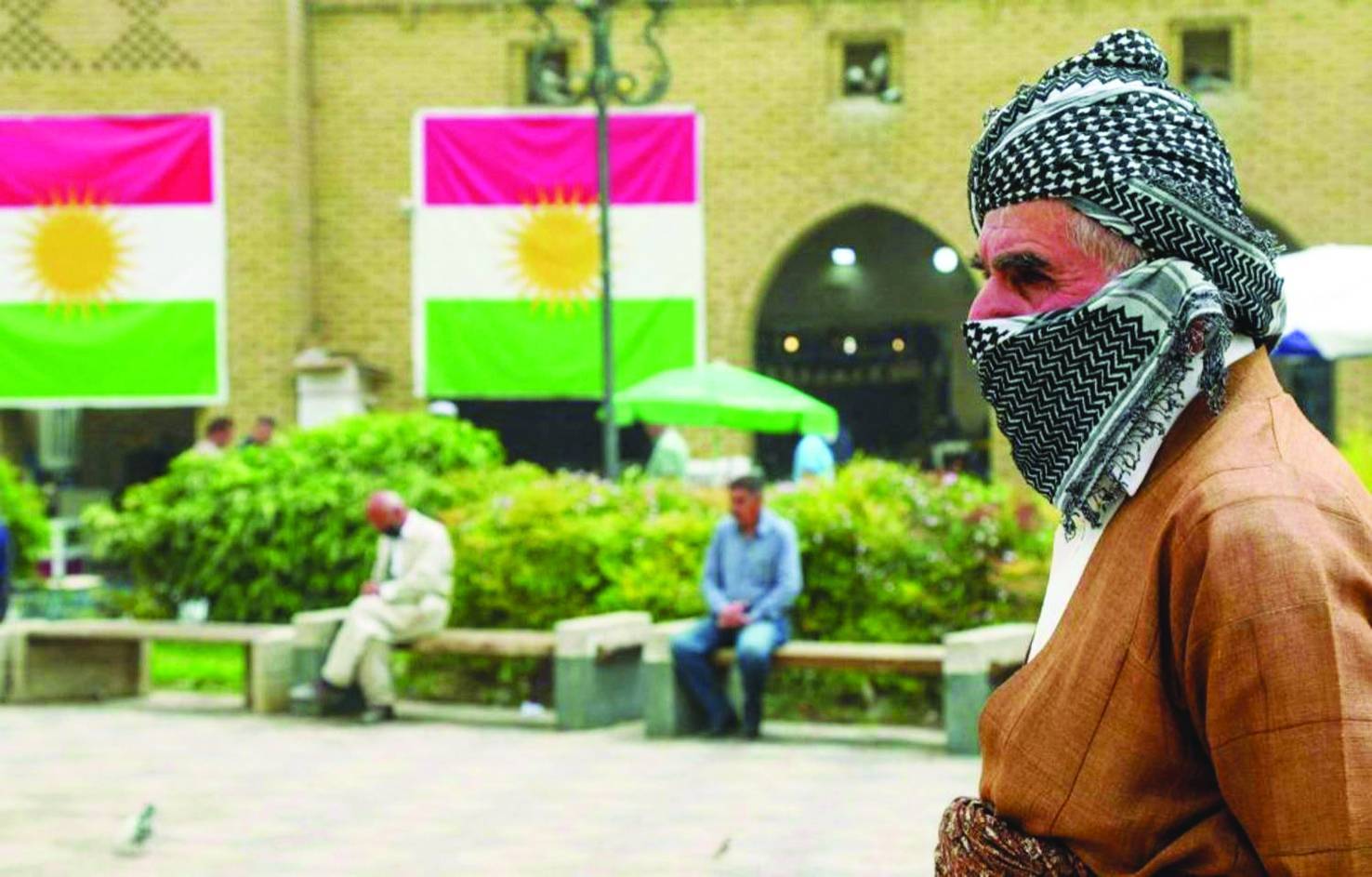

Alwaght- Though the Iraqi Kurdistan region has long lost the fragile unity it had after the end of the civil war of the 1990s and the agreements signed between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) to unify their ranks under a parliamentary government, these days the crisis has gone beyond political differences and is moving to a direct threat to security stability of the autonomous region.

The inefficiency of the legal institutions and processes in settling the political management challenges has put on the federal structure of the Kurdistan region a shadow of division. Now, the danger of return of the clashes of the past is more serious than ever, something we can see its signals in two similar security incidents having taken place in the past weeks in Erbil and Suleimanyeh.

1. Recent developments: from Erbil to Suleimanyeh

The first sign showed itself in July in Khabat district of Erbil. There, the Harki tribe resorted to warned resistance after security forces and Peshmerga affiliated with the KDP moved to arrest Khurshid Harki, the tribe's leader. The clashes prevented the arrest operation as the tribal forces inflicted casualties on the ruling party forces. The observers said the root for the clashes was the differences between Harki tribe with the ruling Barzanis.

A few weeks later, a similar scene unfolded in Sulaymaniyah. Security forces and PUK's Peshmerga moved to detain Lahur Sheikh Jangi, a prominent Kurdish political figure. The move sparked resistance from his supporters, plunging parts of the city into violence and armed clashes. Lahur, who once shared the co-leadership of the PUK with Bafel Talabani, has in recent years emerged as one of the party’s sharpest critics and a symbol of its internal divisions.

Amid deep factional rifts, he went on to establish a new political group, the “People’s Front,” which contested the 2024 Kurdistan parliamentary elections and secured two seats.

While state media framed his arrest as a response to his refusal to appear before the judiciary, his party denied receiving any formal summons. His brother, Aras, warned that any attempt to detain him could trigger armed conflict and drag Sulaymaniyah into chaos.

The developments highlight mounting political and security tensions in Kurdistan region.

2. Roots of instability

The Kurdistan region today is grappling with several interwoven crises:

Partisan divisions and internal competitions: The deep KDP-PUK gaps that have long shaped the power structure in the autonomous region remain the leading destabilizing force. These competitions not only impact the control of strategic regions and economic resources, but also make the executive and security appointments as scenes of disputes.

The first major rift between the two leading Kurdistan parties dates back to May 1994, when Jalal Talabani was still at the helm of the PUK. At the heart of the dispute was the struggle for influence and control over resources, a conflict that spiraled into a full-blown civil war in the region. Fighting reached its peak on August 31, 1996, when Masoud Barzani called on Saddam Hussein’s regime to help him push back PUK forces and reclaim Erbil. The clashes dragged on until September 1998, when the two sides, under US mediation and pressure, finally signed a peace deal.

That agreement has long since lost its teeth as a mechanism for resolving disputes. The political process remains deadlocked, with parliamentary elections postponed for years and the region effectively split into two spheres of power. In April 2021, the PUK even floated the idea of establishing a separate Sulaymaniyah administration in protest against what it sees as the KDP’s domination over both political power and economic resources in Kurdistan.

Local and tribal issues: Some tribes like Harki that have influence in KDP-dominated areas sometimes stand in the face of the party's policies. Disputes over land, resources, and local interests combined with major political gaps lead to armed violence every now and then.

Governance and legitimacy crisis: The regional government's shortcomings in public services, especially civil servants' salaries, massive executive corruption, and restriction of they politics have accumulated social discontent. This discontent has now erupted in the form of protests and local resistance.

3. Impact of recent crises

The fresh developments have left key consequences on the region's political structure:

Undermining parties' internal cohesion: Defection of Sheikh Lahur from the PUK and formation of new parties bear witness to deep gaps within the traditional parties. This has dispersed power, heightened electoral rivalry, and escalated possibility of violent confrontations.

Securitization of politics: issuing arrest warrants to dissenter leaders and continuing tribal monopoly in the Kurdistan's politics between Barzanis and Talabanis has fast transformed the political gaps into security crises. This situation risks armed clashes between ruling parties-affiliated security forces and dissidents.

Future ambiguities

The outlook of the Kurdistan region can be foreseen with worrying scenarios:

Growing violence: The deepening rift between the KDP and PUK, coupled with the unresolved standoff between Erbil and Baghdad, threatens to spill over into violence—most dangerously in contested territories like Kirkuk or areas where disaffected tribes hold sway.

Negative impacts on economy and regional security: Unrest would lead block foreign investment flow and economic development. An atmosphere of instability provides the extremist groups with a breeding ground to mobilize and use the power vacuum.

Role of foreign actors: Regional competition, particularly Washington’s ongoing presence in Iraq, continues to weigh heavily on the Kurdistan's internal dynamics. As outside powers throw their weight behind rival factions, the political landscape grows ever more fractured and volatile.

Conclusion

The Iraqi Kurdistan is at a sensitive juncture. Two recent developments in Erbil and Suleimanyeh are just the tip of the iceberg of a deep crisis having its roots in historical partisan divisions, tribal competition, governance setbacks, and foreign interference. In such conditions, the future of the region mostly relies on its capability to secure home rapprochement and embark on a constructive interaction with Baghdad. Otherwise, risk of further clashes and even return to the biiter civil war days of the 1990s remains standing.