Palestinian prisoner Miqdad al-Qawasmeh has entered his 86th day on hunger strike. He is overcome with weakness and can’t move from his hospital bed, not even to shower or use the bathroom. He suffers from joint, kidney, head, bone, muscular and abdominal pain. He has trouble speaking and has lost more than 75 pounds. Despite his deteriorating health, al-Qawasmeh won’t end his hunger strike, as he and six other prisoners refuse food in protest of their ongoing administrative detention.

Kayed Fasfous has been on hunger strike for 92 days; Alaa Al Araj has spent 68 days without food; Hisham Abu Hawash started his hunger strike 61 days ago; Rayeq Bsharat hasn’t eaten for 56 days; Shadi Abu Akar is now in his 52nd day without food; and Hassan Shouka has been on hunger strike for 27 days. Additionally, at least 250 prisoners associated with the Islamic Jihad organization began a hunger strike on Oct. 13 in protest of their relocation to isolated cells.

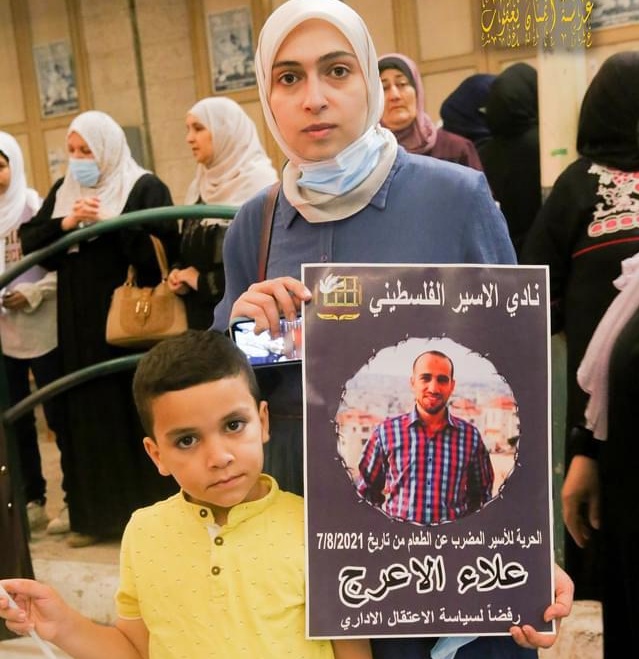

Alaa Al Araj’s son protesting his father’s administrative detention.

Israel’s Supreme Court froze the detentions of both al-Qawasmeh and Fasfous owing to their declining health. Al-Qawasmeh was detained on Jan. 2 and Fasfous was detained in July 2020. However, the prisoners’ relatives and Palestinian government organizations say the Israeli decision isn’t coming from a place of morality but rather from liability concerns. The Commission of Detainees and Ex-Detainees Affairs said in a statement:

The decision to freeze does not mean cancellation, but in fact, it is the disclaimer of the Occupation Prisons Administration and the Intelligence [Shabak] for the fate and life of prisoner Fasfous, and turning him into an unofficial ‘prisoner’ in the hospital. He remains under the guard of the hospital ‘security’ instead of the prison’s guards. Family members and relatives can visit him like any patient according to hospital rules, but can’t move him anywhere.

The commission added that Fasfous’s health is worsening with each day. The 32-year-old is persistently dizzy, has severe fatigue and chest pain, and his blood pressure and blood sugar levels are low. Fasfous also refuses to take supplements or undergo medical tests, saying he didn’t suffer from health problems or illnesses prior to his arrest.

Fasfous and al-Qawasmeh were transferred from the prison clinics to Israeli hospitals. Al-Qawasmeh’s mother, Umm Hazem, told MintPress News that the family received a permit to enter Israel (or 1948-Occupied Palestine). “The [Israel] Prison Service wants to relieve their responsibility from his life in case anything happens,” Hazem said. “It’s not a human-rights thing.”

Administrative detentions increasing

Israel’s policy of administrative detention allows it to imprison individuals indefinitely on secret information without charging them or allowing them to stand trial for a period of six months, with the possibility of renewal. Neither the detainee nor his attorney can access the classified evidence. While Israelis and foreigners can also be subject to administrative detention, the practice is mostly used against Palestinians.

In September, Palestinian prisoner-rights organization Addameer sent an urgent appeal to the United Nations to intervene and pressure Israel to end administrative detention. Addameer’s letter emphasized the fact that administrative detentions have spiked recently. Milena Ansari, Adameer’s international advocacy officer, said:

The Israeli Occupation’s use of administrative detention has drastically increased — especially this year, where arbitrary detention has been a key feature to maintain control over the Palestinians, especially with regards to what was happening in Jerusalem, Sheikh Jarrah, in the West Bank, and especially with the escape of the six prisoners from Gilboa Prison.

In 2020, Israel issued at least 1,114 administrative detention orders against Palestinians, while no less than 759 administrative detention orders were issued from January through June 2021. Currently, 520 Palestinians are held in administrative detention. Ansari suspects the number of administrative detentions will continue surging before the year ends.

What’s become particularly concerning is the dramatic increase in Palestinian children held in administrative detention. Under the Freedom of Information Law, Israeli human-rights organization HaMoked found three minors were administratively detained in January of this year. By June, that number had risen to eight.

Amal Nakhleh, 17, was arrested and placed in administrative detention on Jan. 21, 2020. He was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a rare medical condition that requires constant medical care and monitoring. “Even a child who suffers from health implications is subjected to administrative detention,” Ansari said, adding his detention has been renewed three times. “So you can see the arbitrary use of this against children where according to international law the detention of children should come as the last resort and for the least amount of time possible. But this is in complete contrast [to Israel’s use] of administrative detention.”

For security reasons

Administrative detention is permitted under international law but only within the confines of extreme circumstances related to a national emergency and security purposes. Israel abuses this reasoning by declaring it is in an ongoing (i.e., perpetual) state of emergency.

Addameer argued in a July 2017 publication that Israel uses administrative detention as a form of collective punishment, noting how the number of administrative detainees soared to 8,000 during the First Intifada, a mass Palestinian uprising against the Israeli Occupation lasting from 1987 to 1993. Following the Gilboa Prison break, more than 100 Palestinians were arrested, including family members of the escaped prisoners. And in May Israel issued 155 administrative detention orders during the protests against the forced displacement of Palestinians in Jerusalem and the war on Gaza. According to HaMoked, more than 10 % of Palestinians incarcerated by Israel are administrative detainees.

“When there was an increase of use of force in Jerusalem, with regards to Damascus Gate and Sheikh Jarrah, Israel used administrative detention to rearrest former prisoners under the basis that they might impose a risk on the Occupation,” Ansari said. To her, Israel explains away these arrests by saying “Let’s detain them in the meantime for no reason just to make sure that nothing happens to the security of Israel, which is a 100 times greater than any Palestinian.”

Detainee Hisham’s brother, Saad Abu Hawash, said Hisham was jailed under the guise of security. “The Shabak [Israeli intelligence unit] told Hisham, ‘While you are free, your existence is dangerous for Israelis,’” Saad said. Hisham, 38, was arrested on Oct. 28, 2020 and his administrative detention was renewed in April. He is currently held in Ramleh Prison in Ramla, where Saad said his health is in danger. “The only thing he can move in his body is his tongue, and even that he can barely move because he’s so tired from the hunger strike,” Saad added. “And the moment he drinks water, he vomits it immediately with some blood.” Hisham is also refusing medicine and supplements.

Despite his debilitating condition, Hisham was placed back into a cell, which his lawyer said is dirty, small, and lacks sunlight. This week, Israeli human-rights organization B’Tselem submitted a request to the Ministry of Health to have Hisham transferred to a civilian hospital. At the time of this writing, no government entity had responded to the request

History of hunger strikes in Palestine

Palestinian prisoners started executing hunger strikes in 1968 after Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, as a way to protest ill treatment and conditions inside Israeli jails. This tactic later grew into demonstrating against administrative detention specifically. Palestinian prisoners’ hunger strikes have had varying degrees of success throughout the decades. Some have managed to get their demands met, while others have been subjected to solitary confinement, force-feeding, and banned family visits.

Addameer’s Ansari stated that hunger strikes are used as a last resort mechanism to gain adequate living standards in prison, explaining:

Palestinian prisoners have no other means to fight for their rights but to use their own bodies as a tool. There’s no judicial system to try them fairly. There’s no party inside prison that can share their demands. So the sole item that they can use to protest and fight for their rights is their bodies.

We understand the controversy of how risky it is for their health. But this only makes us understand how desperate prisoners are to gain a bit of dignity when they are detained in Israeli prisons.

‘A normal life’

Asmaa Jalal Quzmar hasn’t seen her husband, Al Araj, since his arrest on June 30.

Asmaa Jalal Quzmar with her son protesting the administrative detention of her husband, Alaa Al Araj.

Asmaa Jalal Quzmar with her son protesting the administrative detention of her husband, Alaa Al Araj.“A special unit from the Israeli forces bombed the main entrance of the house, beat him, and arrested him,” Quzmar recalled. She received permission to visit him in September, but the Israeli Prison Service revoked Al Araj’s visitation rights as punishment for his hunger strike. “He can’t stand. If he drinks water, it will just come out of his nose. He can’t concentrate. And he’s having a hard time breathing,” Quzmar said. Al Araj is also suffering from panic attacks and has lost 44 pounds. Al Araj wanted to go on a hunger strike during his first administrative detention last year, but Quzma convinced him not to. This time around, she couldn’t stop him.

Al-Qawasmeh’s mother, Hazem, hasn’t left his bedside since he was transferred to Kaplan Medical Center in Rehovot. Hazem is begging her son to take supplements but he refuses, knowing that the moment his health improves, the 24-year-old will be sent back to jail. “He would love to live his life freely and have a normal life, not get arrested every few periods,” Hazem said.

Al-Qawasmeh vowed to never go back to prison. This sentiment is motivating him to persist with the hunger strike. “He says, ‘When I don’t do anything, I’m in jail. What will happen when I do something? Even if by the end of it, I’m shahid, I deserve to continue the hunger strike,’” Hazem said. Shahid originates from the Quran and refers to a person dying for what they believe in.

Saad hopes his brother’s hunger strike will exert enough pressure on the Israeli government to release him so Hisham can experience a normal life. Hisham’s family also needs him, Saad said. His mother died when he was in prison in 2008, and now his six-year-old son, who has a kidney problem, may have his kidneys removed.

“It’s very hard to lose a person because of a hunger strike, and for some unfair situation where there are no charges, nothing is happening,” Saad said. “He deserves to have a peaceful life.”