Alwaght- In recent years, China intensified its bilateral and multilateral relations with Central Asian states. It has already signed Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with all Central Asian states, signaling the region’s important geopolitical position in Beijing’s growth-centered foreign policy and global road map for expansion of Chinese trade-economic network. This position even grew larger after eruption of Ukraine war and the consequent large-scale Western sanctions on Russia, to an extent that the region became top alternative access route of China to the European market.

Last year (2022), President Xi Jinping of China visited Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in his first foreign trip since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Last week, the President of Turkmenistan Serdar Bardimuhamedow became the first Central Asian leader, and the second foreign leader, to meet with Xi Jinping in the new year, reaching agreements to upgrade relations to a strategic level. Frequent meetings between the heads of these countries show that China attaches increasing significance to Central Asia, and the region has assumed a more important role in China’s neighborhood diplomacy, especially after the Russia-Ukraine war.

China has been working to develop relations with the five Central Asian countries at three distinct but aligned and overlapping levels. First, comprehensive bilateral strategic partnership agreements. Second, joint regional cooperation, and third, comprehensive cooperation documents between with Central Asia to advance Belt and Road megaproject.

At the first level, China established a strategic partnership with Kazakhstan after 2011, later upgrading it to permanent Comprehensive Strategic Partnership pact. Uzbekistan in 2016, Tajikistan in 2017, and Kyrgyzstan in 2018 joined the pact. Turkmenistan is the last Central Asian nation to join the pact during recent Berdimuhamedow visit to China.

At regional and multilateral level, China proposed China-Central Asia (C+C5) cooperation mechanism which is a new multilateral framework between China and these countries outside the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The first C+C5 Summit is set to be held this year.

At the same time, China has signed cooperation agreements under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with all Central Asian countries in order to synergize between this major transit plan and development strategies in Central Asia. Territorial connection from various routes including cross-border railways, oil and gas cooperation, trade, and investment are very important in BRI-related agreements.

Central Asia is where the operational phase of the BRI began. The China-Central Asia gas pipeline is the longest natural gas pipeline in the world. As of June 2022, the transfer of gas from Turkmenistan to China has exceeded 400 billion cubic meters. Uzbekistan’s 123-kilometer-long Angren-Pap railway and its over 19-kilometer-long tunnel have completely changed China’s transit situation to Central Asia, as it is estimated that after the launch of the new railway line annually 10 million tons of goods will be moved through rail transport.

It is noteworthy that since Turkmenistan shares borders with Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran and the Caspian Sea, the China-Turkmenistan railway will be an extension of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway. China aims to make the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan railway a reality in the coming years. This railway goes from the west to Iran and from the south to Afghanistan. It will be a Eurasian transport artery and a main railroad that connects Central Asia, South Asia and West Asia, and if possible, it can also be extended to Afghanistan to create a railway connecting China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In recent days, China reached an agreement for oil exploitation with Afghanistan. On the other hand, given the increase in exports to China from Central and South Asia, the imbalance in trade between the countries of this line may also be compensated. The cross-border railway can lead to economic dynamism and growth of the region.

What is interesting is that Chinese presence in Central Asia is not limited to state activities and private companies are widely supported by Beijing under a broader strategy. In fact, contrary to Western argument that China exports its development model and imposes it on other countries, in practice China has shown that its economic influence mainly shapes through working with local actors and institutions and at the same time expands through adaptation to local and traditional forms, norms and practices.

According to a research conducted by Carnegie Institute, in Latin America, Chinese companies adapt to local and national labor laws. In Southeast Asia and West Asia, Chinese banks and funds are exploring traditional Islamic credit and financial products, and in Central Asia, Chinese companies are helping local workers upgrade their skills. According to the estimation of this research institute, these adaptive strategies of China, which correspond to local realities and work within their framework, are mostly ignored by Western policy makers.

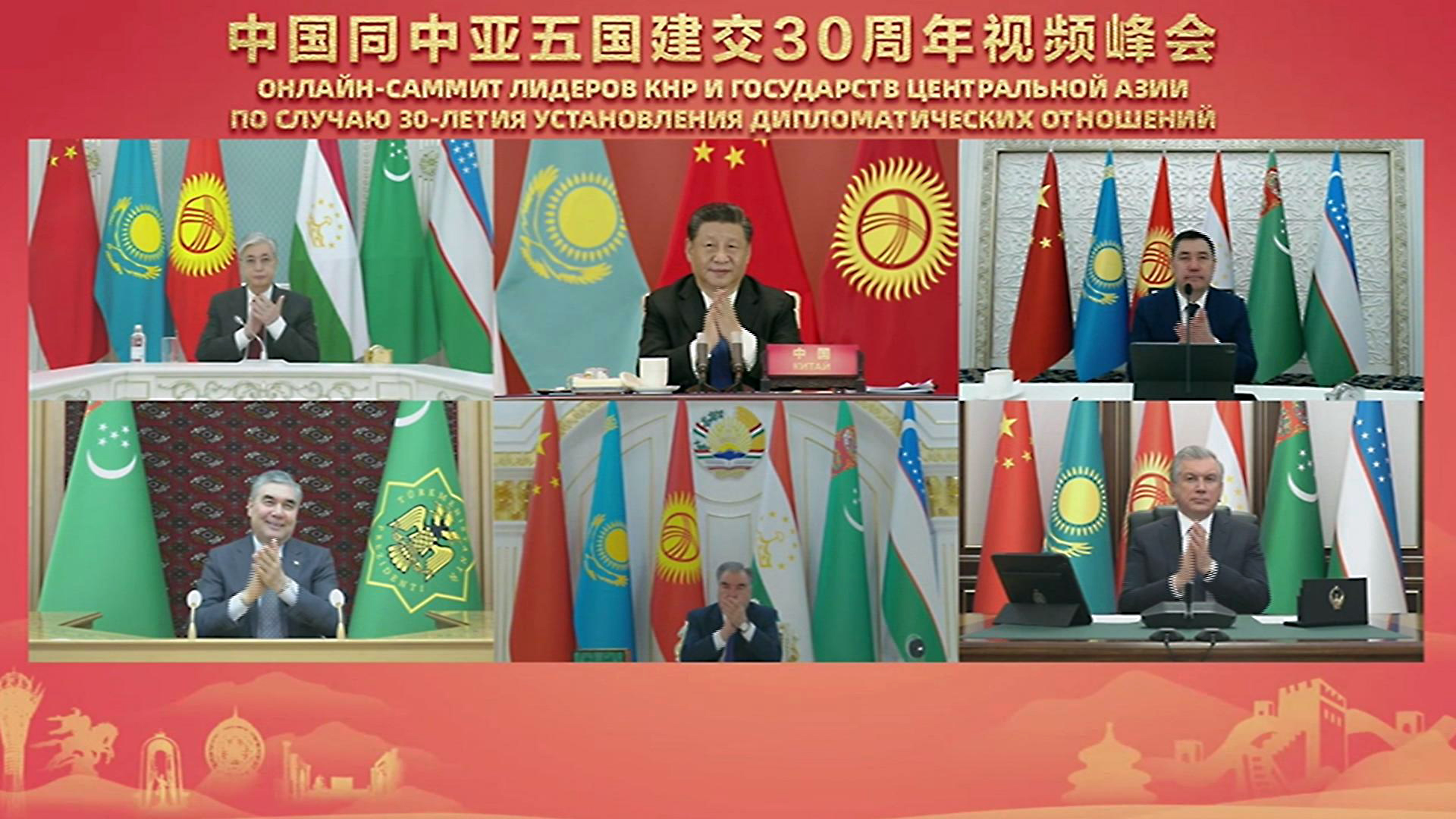

This issue was clearly evident in the video conference speech of Chinese President Xi Jinping on the 30th anniversary the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the five Central Asian countries in January last year.

“No matter how the international situation changes. No matter how much China will make progress in the future. China will always be a reliable and trustworthy neighbor for Central Asian countries. Good partners, good friends, and good brothers.”

Still, China faces challenges and obstacles in its journey to influence in Central Asia. To realize the vision of cross-border railways in Central and South Asia, China is primarily facing the challenge of insecurity and terrorist attacks targeting Chinese workers and interests. Internal political instability, including protests in such countries as Pakistan and Sri Lanka, is another challenge that jeopardizes the sustainable development of joint projects. Additionally, the recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the complex geological conditions in the region are also among the main obstacles to the construction of cross-border railways.

But one of the key challenges is the US interference. The instrument of the American influence over Central Asian countries is the C5 + 1 or CA5 political format, which was created by Washington in 2015.

In February 2020, the US strategy for Central Asia was approved by the Trump administration until 2025. There is ample evidence that this strategy is being pursued by President Joe Biden administration and has retained its importance.

As China’s economic and military power elevates to new heights, the US increasingly shows interest in playing a role in developments in Central Asia with the aim of preventing Beijing from deepening its influence in the region as part of a growing global confrontation between the two heavyweights.

In May 2018, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan made his first official visit to Washington. During this trip, the two countries agreed on the start of a new period of strategic partnership. Several agreements were signed, aiming to develop relations between the two countries in various fields. Among them is a five-year plan for military cooperation, followed by a number of military drills the next months.

Despite such measures by the West and particularly the US to counter Chinese influence in Central Asia, regional states have shown that they lean to cooperation with China driven by Russian concerns about American influence. Uzbekistan, for example, officially refused to host American forces in 2021 after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Actually, in the global competition among powers for influence in Central Asia, so far Beijing has taken the lead by building influence in Eurasia with slow and calculated steps.