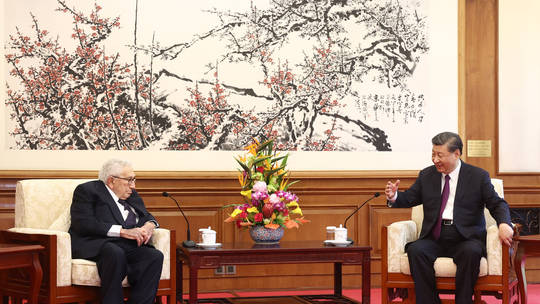

Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, one of the oldest active statesmen in the world at 100, made a visit to Beijing and met with Chinese leader Xi Jinping earlier this month. Although Kissinger’s time in office is controversial in many respects, not least due to allegations of war crimes in a host of Asian countries, China in fact views him positively.

Why? Because Kissinger was one of the key figures in the construction of the US-China diplomatic relationship which followed on from Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking visit to the country in 1972 and his meeting with Mao Zedong. This marked one of the biggest geopolitical shifts of the 20th century, leading to the opening up of China and its integration into the global economy. For this legacy, Beijing is extraordinarily grateful to Kissinger and treats him as an “old friend.” This of course, provides the backdrop as to precisely why he is visiting now, and what this means politically.

Kissinger’s legacy paved the way for an open, stable, and cooperative relationship between the US and China which lasted over 40 years, but that era is now gone. In fact, the mood among some in Washington is to try and dismantle this legacy, framing US engagement with China as a mistake which emboldened a hostile power. That is the message Mike Pompeo sought to convey in 2020 when he was secretary of state. Attempting to reset the US-China relationship into a new “epoch,” Pompeo gave a provocative speech at the Richard Nixon Presidential library in California titled ‘Communist China and the Free World’s Future’.

Since the Trump administration, US-China ties have been going steadily downhill, as strategic competition in the fields of military, diplomacy, and technology have accelerated. The Biden presidency has arguably been more aggressive than its predecessor in some of the measures it has taken. It is little surprise that US politicians see engagement with China as a form of appeasement and politically unfavorable. Therefore, while officials talk of so-called ‘guardrails’ in dialogue with China, their strategic intentions do not change, and neither do they make any concessions in the diplomacy they pursue.

Given this, China is courting Henry Kissinger for a critical reason. He is a living symbol of the relationship Beijing would like to have with Washington, and of what diplomatic ties ought to be like. His presence in Beijing is a political statement. China is displeased with the actions of the US, but ultimately continues to seek engagement, stability, cooperation and openness in its relationship, and nobody is a bigger representation of that than the man with whom it all began, who now believes the US and China must find a path to co-existence to avoid conflict.

In doing so, Beijing calculates that it is a waste of time to try to engage with US politicians directly. The mudslinging and paranoia such attempts are met with is of such a scale that it is damaging for anyone, especially at the level of Congress.

Instead, it has utilized a pragmatic strategy of targeting individuals that it believes can promote stability in the relationship, and inviting them on highly publicized visits. This has included businessmen and public figures such as Tim Cook, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates, who have all visited China in recent months. They are used to convey a message that China is open and still willing to do business, and that ties with the US do not have to be the way they currently are. In addition, these individuals act as back channels. They may not have direct political power, but through their networks and ties they wield influence, especially when it comes to lobbying. Kissinger is elderly, but he is a highly respected member of the foreign policy community.

Despite the geopolitical competition with the US, China is above all cautious of rocking the boat. It is aware that the US political class cannot be swayed in its disposition, but Beijing seeks to contain and minimize its influence through diplomacy, as opposed to confrontation. Empowering Washington’s hawks is one of the worst strategic mistakes China can make. Thus, it is critical to Beijing’s objectives to slow down the ‘decoupling’ and prevent the US from gaining political capital to force other countries, in both Europe and Asia, to get on board with its agenda.

Beijing does not see this as a sprint, but as a marathon. From its perspective, the use of Kissinger sends a message of hope and reconciliation, an idealistic perspective on how US-China ties should be. Of course, there is no turning back the clock, and stability might be all there is to hope for at this stage.