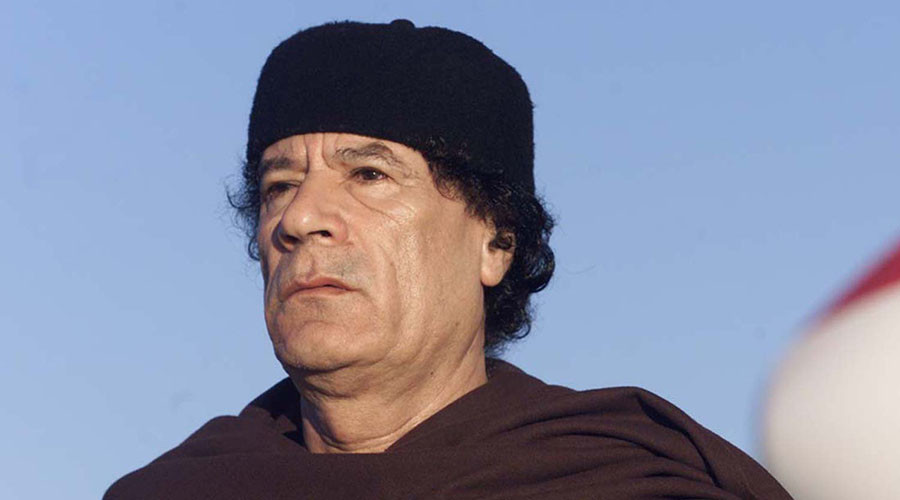

In the 42 years that Colonel Muammar Gaddafi ruled Libya, Western views went from considering him a cartoon villain to believing him a model of international conduct – and back to villain again, when the West backed an armed rebellion against him.

The Libyan Army officer who led the 1969 coup against King Idris I quickly became a thorn in the side of Western powers, nationalizing British Petroleum’s holdings and withdrawing Libyan millions from British banks by 1971. Libya also led OPEC’s oil boycott of the US in 1973, and Gaddafi became an outspoken advocate of the Palestinian cause.

‘Mad dog of the Middle East’

It was under the Reagan administration that open hostilities flared up between Washington and Tripoli, however. In 1981, the US Navy intensified what it called “freedom of navigation” patrols in the Sirte Gulf, which Gaddafi had declared exclusive Libyan waters. US fighters shot down Libyan jets over Sirte on two occasions, in August 1981, and again in January 1989. In March 1986, a US Navy task force entered the Gulf and sank several Libyan Navy ships, killing 35 people.

Libya was blamed for the bombing of a discotheque in Germany in April 1986, which killed 2 US soldiers and injured 79 more, along with many civilians. President Ronald Reagan called Gaddafi a “mad dog of the Middle East,” and ordered the US bombing of Libya, called “Operation El Dorado Canyon.” Gaddafi’s government was listed as a state sponsor of terrorism, and placed under a sanctions regime.

Gaddafi was also accused of organizing the bombing of Pan Am flight 103, which crashed outside of Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988. In 1992, the UN imposed sanctions against Libya, demanding it turn over those responsible for the attack.

Libyans were even presented as terrorists in US popular culture, notably in the 1985 movie “Back to the Future.”

‘Model for others’

By 2003, however, it seemed like the tide had turned. Gaddafi had declared his intent to surrender Libya’s atomic and chemical weapons materials, and pay compensation to victims of the Berlin disco bombing and the Pan Am Lockerbie flight.

Libya’s decision to abandon its weapons programs should become “a model for other proliferators to mend their ways and help restore themselves to international legitimacy,” Assistant Secretary of State for Verification and Compliance Paula DeSutter told the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee in May 2005. The US removed Libya from the list of state sponsors of terrorism in 2006.

Gaddafi is “campaigning for the reintegration of his country into the international community,” French PM Francois Fillon said in December 2007, as the Libyan leader was visiting Paris. “All those who want to lecture us should carefully weigh their words.”

In 2008, Italy offered Libya $5 billion in reparations for occupying the country between 1911 and 1941, and the government of Silvio Berlusconi signed several lucrative trade deals with Gaddafi. Libya also agreed to stem the flow of immigrants from Africa, passing through the country on their way to Italy and the EU.

Italian President Giorgio Napolitano said he had heard Gaddafi “speak with great moderation and a sense of duty when it comes to the most difficult problems facing the African continent.”

In 2004, Libya paid $35 million in compensation to the victims of the Berlin disco bombing. In 2008, another $1.5 billion was paid into the fund to compensate victims of Pan Am 103 and Americans who died in the disco bombing, among others. Libya served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2008-09.

‘Killing his own people… lost all legitimacy’

In February 2011, following the mass demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt, a rebellion against the Libyan government began in Benghazi, the country’s second-largest city and the historical capital of the Cyrenaica region. Within days, the US and the European powers that had previously sang Gaddafi’s praises turned on him.

Citing UN Security Council Resolution 1973, which called for a no-fly zone over Libya to “protect civilians,” the US, UK, France and several other powers began bombing Libya on March 19, 2011. The US had strategic command of the intervention, which was codenamed “Operation Odyssey Dawn.” Alongside the air strikes and cruise missile attacks, special forces from the UK, France, Italy, Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates worked with the rebels inside Libya.

“We are doing it to protect the civilian population from the murderous madness of a regime that in killing its own people has lost all legitimacy,” said French President Nicholas Sarkozy.

“Colonel Gaddafi has made this happen. He has lied to the international community… He continues to brutalize his own people,” said British Prime Minister David Cameron, adding, “We cannot allow the slaughter of civilians to continue.”

The intervention’s purpose was “to protect civilians and it is to provide access for humanitarian assistance,” said US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper gave away the game as regime change, however, when he said that Gaddafi would “simply will not be able to sustain his grip on the country” if his armed forces were destroyed.

“The nature of this leader and the nature of his regime is they will massacre every single individual they even remotely suspect of disloyalty,” Harper added.

US President Barack Obama simply skipped over the previous decade of relations with Libya, justifying the bombing to the American people on March 28 by saying that Gaddafi “has denied his people freedom, exploited their wealth, murdered opponents at home and abroad, and terrorized innocent people around the world – including Americans who were killed by Libyan agents.”

Gaddafi himself seems to have been unaware of this speech when he wrote Obama on April 6, asking him personally to stop the bombing and reminding him that “democracy and building of civil society cannot be achieved by means of missiles and aircraft, or by backing armed members of Al-Qaeda in Benghazi.”

'We came, we saw, he died'

Gaddafi’s words fell on deaf ears. The NATO-backed rebellion succeeded in seizing almost all of the country by October 2011. On October 20, Gaddafi tried to break out of Sirte, but his convoy was bombed by NATO aircraft. He was captured, tortured and killed by militants loyal to the Western-backed National Transitional Council government, proclaimed the month prior.

“We came, we saw, he died,” quipped Hillary Clinton, learning of Gaddafi’s death during a CBS interview.

Libya plunged into chaos, with factions in Tripoli and Benghazi fighting each other, and Islamic State (IS, formerly ISIS/ISIL) raising its flag over Sirte.

“Today there is no government of Libya. It’s simply mobs that patrol the streets and kill one another,” Virginia State Senator Richard Black told RT. “We were willing to absolutely wipe out and crush their civilization.”

“The Libyans had an incredibly high standard of living, the highest in Africa. When I first went to Libya in 1986, I was amazed by the empowerment of women,” international lawyer Francis Boyle told RT. “What I saw in Libya was that women could do anything they wanted to do.”

Among the world leaders saddened by Gaddafi’s death was Nelson Mandela, the first black president of South Africa. “In the darkest moments of our struggle, when our backs were to the wall, Muammar Gaddafi stood with us,” he said.

In 1997, Mandela defied the UN embargo to visit Gaddafi and thank him for his support during the anti-apartheid struggle. US President Bill Clinton called the visit “unwelcome.”

“No country can claim to be the policeman of the world and no state can dictate to another what it should do,” replied the former political prisoner.