The answer plainly is no. But that’s the process America’s got. Every attempt to modify it – not that there have been very many of consequence – has failed. So here we are again, in the midst of the gaudiest, most inefficient rite of democracy on earth, fought under rules laid down almost 230 years ago but in which, in practice, anything goes.

The campaign begins virtually the moment the last vote has been cast in the previous Congressional mid-term elections – and even before that an aspiring candidate may be quietly putting the bones of a campaign together, lining up donors and so on.

It is argued that in a presidential system a protracted process is required. After all, a candidate may be a virtual unknown (see Jimmy Carter in 1975), unlike in a parliamentary system like Britain’s where a potential prime minister usually has served in the Commons, and maybe government, for a decade or more. In the US a long campaign, it is said, proves the mettle of the man, flushing out his strengths, his weaknesses, the skeletons in his cupboard. But two years?

Further disorder is built into the system by the confederal nature of the US. An American presidential election is not one election but an amalgam of 50 elections, conducted by individual states that jealously cling to their right to organize them as they see fit, right down to their own voting hours, and ballot papers. Remember those hanging chads and butterfly ballots in Florida 2000? But more of that later.

The media

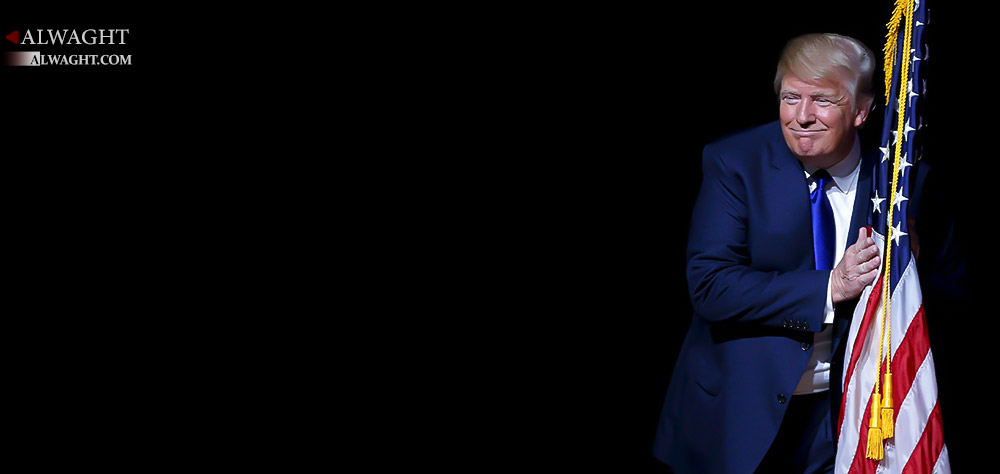

Then there’s the media. As this 2016 cycle has proved, the election is part of the entertainment business. The more outrageous the candidate (see Mr Trump), the more the coverage. TV ratings for debates have never been higher – not because of a newly discovered yearning to learn about issues, but in the hope of a dust-up between candidates.

It’s not about foreign policy, or the ins and outs of education reform, but personality: who would you rather have a beer with? It’s a horse race, not a policy seminar, driven by half a dozen polls a day. For the networks, all this means money. So why not drag it out as long as possible?

The money

Ah yes, money. 2016 will beat all spending records: $5bn – maybe more, now that a Supreme Court ruling has removed virtually every constraint, in the name of free speech. True, there’s a body named the Federal Election Commission that’s supposed to control the money side of things. But the FEC is a toothless tiger, permanently deadlocked – like Washington in general – between its three Democratic and three Republican members. “Dysfunctional? It’s worse than dysfunctional,” says its former chairwoman, Ann Ravel.

Once upon a time, under post-Watergate campaign laws, candidates used to rely on federal matching funds to finance their campaigns. But that facility runs only to $50m for the primaries and $100m for the general election – chicken feed against the $750m that the network of the Koch brothers alone have budgeted for 2015/2016 political spending for the Republicans.

The numbers

Assume you’ve got the money lined up. You’re off and running. But not to powerhouse states like California, New York or Texas. Your first, and all-consuming focus is on Iowa and New Hampshire, two small, white and unrepresentative states that have a disproportionate bearing on selecting a party nominee. A set of regional, or even a single national primary? Forget it.

Assume again that all those months of town halls, visits to diners and flattery of voters pay off, and like Trump, Cruz, Bush, Clinton, Sanders, Kasich and Rubio did this week, you’ve stamped your ticket out of New Hampshire. Four months of primaries lie ahead, during which you amass delegates for the nominating convention in July.

But calculating their numbers is a brain-twister in itself. If you’re a Democrat, there are 4,051 pledged and 713 unpledged, or “super-delegates,” meaning 2,383 is the number needed to win. Delegates are awarded on a proportional basis, but only to candidates who won at least 15 per cent of the vote.

If you’re a Republican, the maths is no less tricky. 1,237 is the magic number. Until mid-March delegates are allotted on a proportional basis. Thereafter, starting with Florida on March 15, it’s winner-take-all.

Oh and one other thing. If no-one has a majority going into the convention, those pledged delegates are pledged only for a first ballot. After all the huffing and puffing, the millions of votes hard won, the zillions of dollars spent, everything might be settled by party power brokers.

The states

But assume you successfully navigate these hazards, you’ve been crowned as nominee, and embark on the general election campaign. It’s supposed to be a national campaign. It’s not. The largest states (California and Texas, seen as Democratic and Republican shoo-ins respectively) hardly get a look in. The battle is fought in around a dozen “swing” states, among them Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, which do actually change hands.

The votes

Finally the big day comes, on Tuesday, 8 November. And why Tuesday, you ask, when Sunday – the day used by most other democracies (but not Britain) – would be so much more convenient? The answer is something to do with Sabbaths and market days in 19th century America.

That surely is one reason for the chronically low turnout here (the US ranks 31st out of the 34 member countries of the OECD.) Another is voter suppression, especially of blacks and minorities, by Republican states, mainly, but not solely, in the South.

Finally though you get to vote. Except you’re voting not for the president, but for electors who will elect him, the members of the infamous electoral college.

It was that body, combined with the US Supreme Court, which determined that even though Al Gore won 540,000 more votes, George W Bush won the 2000 election. To this day, no-one knows who carried Florida, though the Court awarded the state to Bush, banning a recount.

Over the years, hundreds of attempts to replace the Electoral College with direct universal suffrage have failed. The latter, of course, is far too simple and transparent. Crazy, isn’t it?

It’s about personality not policy: who would you rather have a beer with?

Sources: http://www.independent.co.uk