Alwaght- Israeli regime has carried out at least 2,700 assassination operations against Palestinians, Egyptians, Syrians and Iranians since World War II, a new book reveals.

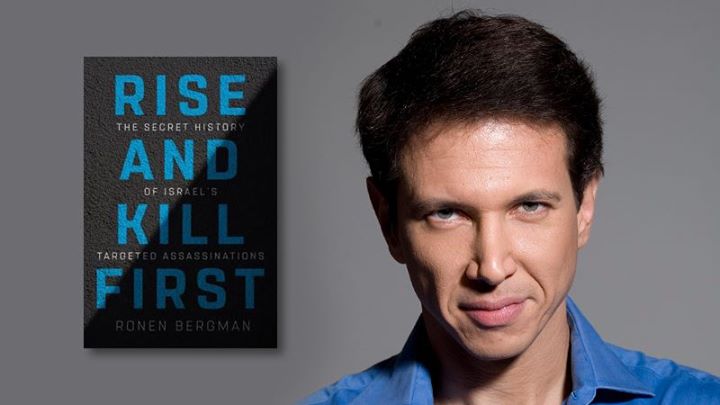

Ronen Bergman, the intelligence correspondent for Yediot Aharonot newspaper, persuaded many agents of Mossad, Shin Bet and the military to tell their stories, some using their real names. The result was Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations, an over 600-page book that also includes assassinations by paramilitary organizations that were operating before the regime proclaimed existence in 1948.

Relying on around 1,000 interviews and thousands of documents, Bergman chronicles many techniques and asserts that Israeli regime's assassination machine has adopted, including poisoned toothpaste that takes a month to end its target’s life; armed drones; exploding cell phones; spare tires with remote-control bombs; as well as assassinating enemy scientists.

The regime has killed many Palestinian leaders, including those with the Gaza Strip-based resistance movement of Hamas.

The book suggests that Israel used radiation poisoning to kill Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian leader who was the founder of the Fatah movement, investigations into whose murder continue up to date.

The Israeli spy agency Mossad, the author says, tried to prevent his progress in authoring the work by approaching his subjects and warning them against giving interviews.

The book’s title comes from the ancient Jewish Talmud admonition, “If someone comes to kill you, rise up and kill him first.” Bergman says a huge percentage of the people he interviewed cited that passage as justification for their work. So does an opinion by the military’s lawyer declaring such operations to be legitimate acts of war.

Bergman calls the Israeli assassination apparatus “the most robust streamlined assassination machine in history.” He says many of the Israeli techniques were later adopted by the US.

The book gives a textured history of the personalities and tactics of the various secret services. In the 1970s, a new head of operations for Mossad opened hundreds of commercial companies overseas with the idea that they might be useful one day. For example, Mossad created a Middle Eastern shipping business that, years later, came in handy in providing cover for a team in the waters off Yemen.

In the name of state security, Israeli officials didn’t just walk the line of legality, they trampled it. “Summary executions of suspects who posed no immediate threat, violations of the laws of Israel and the rules of war — were not renegade acts by rogue operatives,” Bergman writes in “Rise and Kill First.” “They were officially sanctioned extrajudicial killings.”

The chief defense correspondent for Yedioth Ahronoth, Bergman has a reputation as an indefatigable journalist who has developed hundreds of informed sources in the defense establishment over the past two decades. He is in a privileged position — defense correspondents get regular briefings from high officials but must submit their reports to the military censor’s office, which often excises much of the juiciest stuff. But Bergman has a secret weapon: the chatty, introspective men (yes, except for the late Golda Meir, they’re all men) he writes about. He clearly has excellent sources in all three components of the secret killing machinery: the Directorate of Military Intelligence, the Mossad spy agency and the Shin Bet internal security service. “On the one hand, nearly everything in the country related to intelligence and national security is classified as ‘top secret,’ ” he writes. “On the other hand, everyone wants to speak about what they’ve done.”

The general impression he gives about Israeli about Israeli authorities is over-caffeinated warrior princes who constantly seek creative new ways to identify and kill their enemies, convincing themselves that they are not only the best at what they do but also the most moral. They agonize over the personal burden of killing innocent civilians alongside their enemies, but inevitably they justify their own deeds — and cover up their occasionally embarrassing miscalculations.

Bergman paints a chilling portrait of the evolution of the assassination program, as Israeli operatives became more and more skilled at striking their targets with car bombs, mail bombs, airstrikes, explosive devices attached to cars by operatives on motorcycles, and even poisoned baklava. Initially, he writes, each proposed killing required a “Red Page” signed by the prime minister.

But when the process proved too time-consuming, the heads of the secret agencies created a workaround “by which an assassination was called something else so that it would fall under a different decision-making protocol.” The program came complete with its own Orwellian vocabulary: The killing of innocent civilians was labeled “accidental damage,” while the assassinations became known as “targeted preventive acts.”