Third-grader Farah Abbas al-Halimi didn’t get the UNICEF backpack or textbook she was hoping for this year. Instead, she was given an advanced U.S bomb delivered on an F-16 courtesy of the Saudi Air Force. That bomb fell on Farah’s school on September 24 and killed Farah, two of her sisters, and her father who was working at the school. It will undoubtedly have an irrevocable effect on the safety and psyche of schoolchildren across the region.

Over the course of Yemen’s pre-war history, which locals fondly refer to as the happy Yemen years, never has an entire generation been subjected to the level of disaster and suffering as that levied upon Farah’s generation by the Saudi-led Coalition, which has used high-tech weapons supplied by the United States and other Western powers to devastating effect since it began its military campaign against Yemen in 2015.

Last week a new school year in Yemen began, the fifth school year since the war started, and little has changed for Yemen’s schoolchildren aside from the fact that the Coalition’s weapons have become more precise and even more deadly, leaving the futures of the country’s more than one million schoolchildren in limbo.

"I want to go to school, I can’t wait any longer,” a relative of six-year-old Ayman al-Kindi told MintPress, recalling how Ayman, surrounded by proud family members, waited impatiently to leave for his first day of school. Ayman would never make it to school; in fact, he never even made it outside. “Ayman wanted to become a doctor but a bomb took him away from school. What these American bombs do to our children is terrifying,” his relative told us.

In late June 2019, Coalition aircraft targeted Ayman’s family home located on their farm in the Warzan area, south of Taiz province in southwestern Yemen. Six of Ayman’s family members were killed, including three children aged 12, nine and six. According to Amnesty International, the laser-guided precision weapon used in the attack was made by Raytheon. Amnesty’s arms experts analyzed photos of the remnants of the weapon recovered from the scene of the attack by family members and identified it as a U.S.-made 500-pound GBU-12 Paveway II.

The use of a U.S.-made weapon in the attack on the al-Kindi home was no anomaly: most of the weapons possessed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which between them have carried out a quarter of a million raids on Yemen since the beginning of the war, are American-made. This week, families who lost loved ones in Coalition airstrikes held an exhibition called “Criminal Evidence” in the city of Sana`a. The event was an opportunity to consolidate evidence of potential war crimes and prompted hundreds of Yemeni civilians to attend the event with remnants of U.S.-made weapons in tow, remnants recovered from the rubble of the attacks that killed their loved ones.

Photos from an Amnesty investigation show the Al-Kindi home and the Raytheon bomb that destroyed it.

Charles Garraway, a former military lawyer and one of the experts behind the report, recently told PBS, “We have a war that’s going on. It’s causing immense suffering and frankly most of that suffering is caused by arms.” Garraway continued, “The tragedy in Yemen is so awful at the moment that somehow one has got to reach some form of settlement to stop the war.”

Despite the abundance of evidence proving that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have routinely targeted schools and other civilian facilities, the United States continues to replenish the Coalition’s arsenal. Earlier this year, the Trump administration tried to force through an $8.1 billion arms deal to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan; and, despite growing opposition within his own government, President Donald Trump seems determined to maintain the flow of U.S. weapons to Saudi Arabia and its allies.

Not your normal “back-to-school” day

Eleven-year-old Mohammed AbdulRaham al-Haddi is one the few schoolchildren to have survived the horrific August 9, 2018, Saudi airstrike on a school bus on the outskirts of Dahyan in Yemen’s northwestern province of Saada. The attack killed more than 35 of his classmates, but Mohammed miraculously survived. Today, he returns to school for the first time since the deadly attack, but to an underserved school and without his classmates. Al-Faleh, Mohammed’s new school, lies nestled in a dusty valley near Yemen’s northeastern border with Saudi Arabia

Mohammed al-Haddi, a survivor of an August 2018 airstrike on a school bus, returns to school for the first time since the attack. Ali al Shurgbai | MintPress

The attack on Mohammed’s school bus was carried out using a Mark 82 (MK-82) bomb, jointly manufactured by U.S. weapons companies Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics. The MK-82, along with other general-purpose MK-series bombs, has been sold to the Saudi-led Coalition by the United States through a series of contracts made in 2016 and 2017. In addition to last year’s atrocity, the Coalition has used the MK-82 to target Yemeni civilians in the past, such as its bombing of a funeral in 2016 that left over 140 dead and 525 wounded.

As the war in Yemen enters its fifth year, the tragic consequences of these weapons deals are difficult to describe, but their effects are noticed everywhere. Some 3,526 educational buildings have been at least partially destroyed by bombs since the war began, with most yet to be rebuilt. Of those, 402 were completely destroyed, according to a new field survey conducted by the Ministry of Education. Approximately 900 of Yemen’s schools are still being used as shelters for the internally displaced. And 700 schools have been closed as a result of ongoing clashes.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that two million children are out of school in Yemen. “A fourth of the two million Yemeni children have dropped out since the beginning of the Saudi war in March 2015,” UNICEF representative in Yemen Sara Beysolow Nyanti said in a statement released last Wednesday.

Beysolow raised concerns about the future of Yemeni children, saying:

[They] face increased risks of all forms of exploitation including being forced to join the fighting, child labor and early marriage. They lose the opportunity to develop and grow in a caring and stimulating environment, ultimately becoming trapped in a life of poverty and hardship".

According to the Geneva-based human rights monitoring organization, SAM, four hundred thousand schoolchildren in Yemen suffer from acute malnutrition, exposing them to the risk of sudden death, 7 million schoolchildren face hunger, and more than 2 million do not go to school.

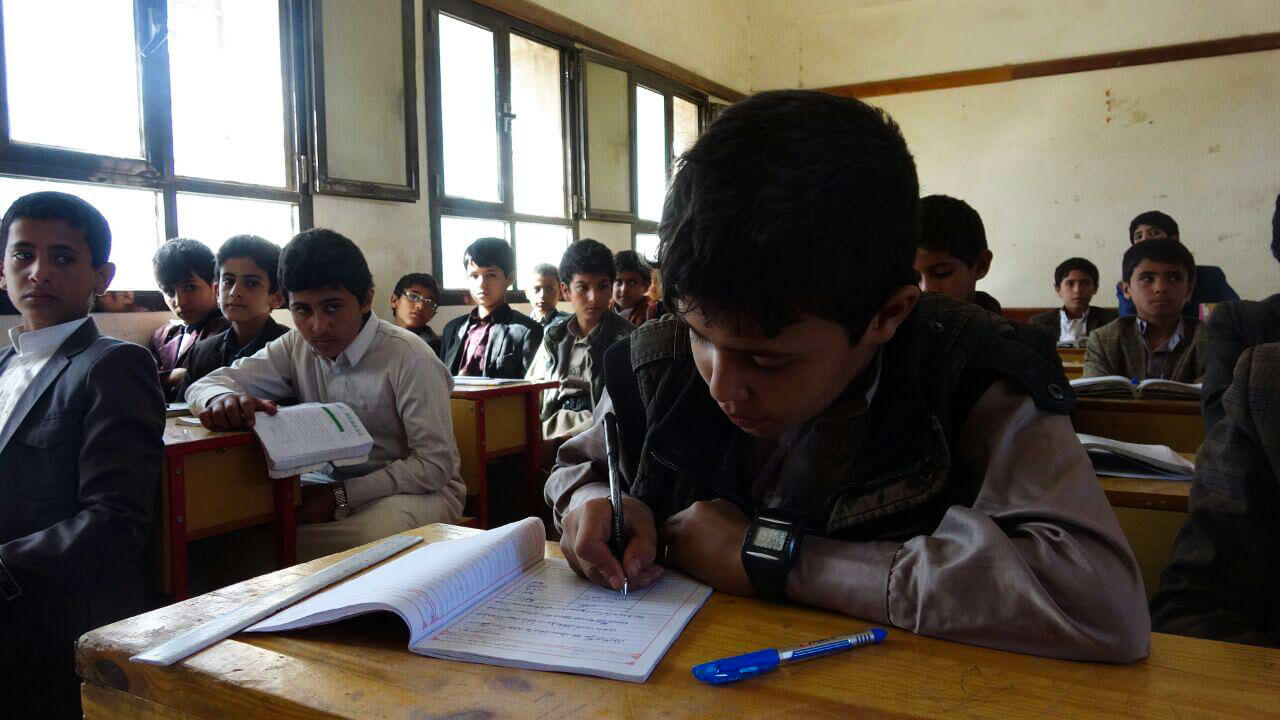

Even before the war began, the education system in Yemen, the Arab world’s poorest country, was not in good health; a lack of equipment, unqualified teachers, and a shortage of textbooks plagued the country’s schools, which were bursting at the seams with overcrowding. Coalition bombs and a blockade supported by the United States have effectively destroyed what was left, just as schools were beginning to show signs of recovery.

Many of Yemen’s teachers have not received a paycheck in years and some, unable to eke out a living, have sought work as soldiers-for-hire on Yemen’s battlefields, leaving millions of children without prospects for education and the country as a whole with a 70 percent rate of illiteracy. Beysolow warned that the education of a further 3.7 million Yemeni children is at risk, as teachers have not received their salaries for over two years, adding that one fifth of schools in Yemen can no longer be used as a direct result of the conflict. “Violence, displacement and attacks on schools are preventing many children from accessing school,” she said.

In a bid to stop teachers from leaving schools, the Ministry of Education, based in Sana`a, has imposed a fee on students of $2 per month to pay teacher salaries, but that seemingly nominal fee has added a huge burden to families with more than one child, many of whom are living in extreme poverty as a result of the war and siege. “I have six students, meaning that I need to pay $12 a month; I can’t save that amount,” one mother told us. She lost her husband in the clashes that erupted between the former president Ali Saleh and opposition tribes on Hasabah Street in 2011. Now, her only source of income is begging and it is not enough to feed her six children, let alone send them to school.

To make matters worse, just weeks before the new school year began, the Saudi-led Coalition prevented 11 oil tankers from entering Yemen. The move sparked an acute shortage of fuel, which meant that school buses could no longer run, leaving even those with the means to pay school fees unable to send their children to school.

The severe psychological toll

The effect of U.S.-made weapons upon Yemen’s children does not end there. Children who have survived the fighting are often left with physical disabilities and severe and chronic psychological symptoms, turning their environment into the worst place in the world, according to UNICEF.

Beyond the direct casualties from airstrikes, the largely unnoticed and unrecorded (by the world) sounds of explosions and buzzing warplanes are leaving Yemen’s children with irreversible psychological damage.

Terrified children take cover at the entrance of a cave used as makeshift shelter in the Maran border area, September 30, 2019. Taha al Shurgbai | MintPress

Like other students, Mohammed often gets distracted while at home or sitting in class, unable to focus and laden with severe anxiety. While students the world over occupy their minds with the day-to-day matters that should accompany adolescence, Yemen`s students, especially those who live in border districts, are filled with an ever-present fear of an impending airstrike.

Since the school year began on September 15, the Saudi-led Coalition has reportedly dropped more than a thousand bombs and missiles in 400 separate airstrikes targeting border districts including Sadaa, Hajjah, Sana`a, Amran, Dhali, and Hodeida. The hundreds of sorties are accompanied by frightening whizzing noise and have left great panic in the hearts of civilians, especially Yemen’s schoolchildren.

"Before the war, the sound of planes meant happiness for families who were expecting loved-ones returning [from abroad], but now the sound of planes mean destruction, death, blood,” Dr. AbdulSalam Ashish, a consultant for psychological and neurological diseases, told MintPress. Dr. Ashish continued, “Now, the planes bring nothing but fear and panic and are a reminder of tragedies and crimes that were committed with U.S., British, and French weapons".

“It was 1:45 p.m., when we heard a missile strike; we were able to calm the students down but when the third strike hit we lost control of the students as they began to scream and chaos spread throughout the school,” Hana Al Awlaqi, a school agent at the “Martyr Ahmed Abdul Wahab Al Samawi” School, said, recounting the moment a Saudi attack took place just tens of meters away from the school. “The sound of the fourth bomb made matters worse, as the school was being broken into by panicked parents and many teachers were fainting.”

School children react to bombs dropped outside of the Martyr Ahmed Abdul Wahab Al Samawi school on Nov 11, 2017. Mohammed al Alkabsi | Yamanyoon

Al Awlaqi went on to say that many students convulse into spasms when they hear the sound of airplanes, while others have refused to come back to school. “The sound of an explosion or the buzz of the aircraft stays in the mind. The sound of an aircraft can send these children into severe panic attacks and anxiety,” Dr. Ashish confirmed.

Jalal Al-Omeisi, a pediatric nurse at the Psychiatric and Neurological Hospital in Sana`a told MintPress that most of the cases that arrive at the hospital are from areas subjected to intensive Saudi Coalition raids, such as Sana`a, Hodeida, and Saada, as well as the border areas. Al-Omeisi went on to say that most medics lack the training to deal with the complex psychological issues that these children are developing.

Such experiences in children go well beyond the temporary impact on their education and, without proper care and the knowledge necessary to address treat these psychological issues, many will suffer life-long consequences that hinder their ability to obtain an education. This is especially true in light of the lack of programs, centers or hospitals for the rehabilitation of war-affected children in Yemen.

Asking Americans to open their eyes

Schoolchildren living along Yemen’s porous border with Saudi Arabia and throughout its southern districts face a reality even more grim than that faced by their peers. Many are recruited or even forced to join the fight to defend the Saudi border via local trafficking networks, which funnel children into training and recruitment camps in the southern Saudi provinces of Jizan and Najran, as well as to Yemen’s southern districts.

According to a recent report by SAM, Saudi Arabia has been enlisting thousands of Yemeni children to fight along its southern border with Yemen over the past four years. Those have who died as a result of the fighting at the border are often buried in the Kingdom without their families’ knowledge. At least 300 had to have their limbs amputated as a result of their military injuries.

A 17 year-old boy holds his weapon in High dam in Marib, Yemen, July 30, 2018. Nariman El-Mofty | AP

MintPress managed to speak to dozens of school-aged Yemeni children who were captured in a recent Houthi operation that saw thousands of militiamen, including dozens of schoolchildren, and Saudi officers taken into captivity. Fifteen-year-old Adel was among those captured. He left his home in the southern city of Taiz, chasing promises of a regular paycheck of up to 3,000 Saudi riyals ($800). Adel told MintPress:

We were left alone in Wadi Abu to face our destiny. Older recruits were fleeing on pickup trucks and armored personnel carriers; Saudi airstrikes hit us as we were surrendering to the Houthis.”

Saudi warplanes targeted the captured mercenaries in Wadi Abu Jubarah, killing more than 300 of their own recruits.

Adel, who left school for the promise of a paycheck, went on to say, “Me and the others were recruited to wash the clothes of Saudi soldiers but they gave us rifles and forced us to go to battlefields.” When asked what he would do when freed, Adel said simply, “I want to go back to my mom and school. I don’t want to fight.”

The recruitment of Yemeni children by Saudi Arabia is not without precedent. Although the Kingdom signed the international protocol banning the involvement of children in armed conflict in 2007 and again in 2011, it was accused of recruiting Sudanese children from Darfur to fight in Yemen on its behalf as late as 2018.

Mohammed, who often visits the memorial to his classmates located only a few hundred meters away from his new school, said he will continue to attend school every day, regardless of how much bombing there is. He asked that Americans open their eyes to see what their weapons are doing to Yemen’s children.

Source: MintPress News

By: Ahmed AbdulKareem